The following blog post is an excerpt from a blog post entitled ‘The Grand Illusion (Part 11) ~ South Armagh’ that you can read HERE.

I’m posting this excerpt on the anniversary of a successful outcome to a counter-terrorism operation, that occurred on the 10th April 1997 in the south of County Armagh, Northern Ireland. I think it provides a glimpse into the world of counter-terrorism but it may also provoke some thoughts on political expediency and morality.

Bandit Country

Quite a few people reading this blog would probably have difficulty in locating County Armagh on a map and even greater difficulty in quickly locating certain place names along the Armagh / Louth border. It’s a rural area with small towns and villages. It looks like an unlikely source of the terrorist violence for which it became infamous and that violence was not confined to Northern Ireland.

South Armagh was known as ‘bandit country’ due to the level of terrorist / criminal activity and the related dangers and difficulties that the police and military faced when operating in the area. The ultimate objective of hardliners in the Provisional IRA (PIRA) was to make the entire border region virtually ungovernable.

As we are already on a virtual visit of South Armagh, this might be an appropriate time to give people who are unfamiliar with the area, a brief introduction to the nature of the terrorist threat that existed, as well as how it was countered by the security forces.

England

The following three terrorist bomb attacks in the 1990s, are just some examples of what came out of South Armagh. This might give you a sense of what the security forces in Northern Ireland were dealing with each day whilst engaged in counter-terrorism. It might also give you some understanding of what hardliners in PIRA had been hoping to achieve when they plotted to smuggle three hundred tonnes of weapons and plastic explosives from Libya. Thankfully their smuggling operation only managed to import around half of the intended armaments.

In April 1992, PIRA detonated a bomb in London that consisted of approximately 1000lbs of ammonium nitrate. Around 100lbs of Semtex plastic explosives was used as a trigger or booster. The bomb had been transported inside a lorry. The Baltic Exchange building was partially demolished and other buildings nearby were badly damaged. Three people were murdered, one of whom was a fifteen year old girl who had been siting in a parked car. Over ninety people injured.

In April 1993, PIRA detonated a bomb in Bishopsgate, London. The one tonne bomb contained ammonium nitrate. The bomb had been smuggled into England from South Armagh, then placed in a truck and concealed under tarmac. The bomb caused extensive damage to surrounding buildings, with a final repair bill estimated to be around one billion pounds. A press photographer was killed by the blast and over forty people were injured.

In February 1996, PIRA announced the end of a seventeen month ceasefire with the detonation of a huge bomb in London’s Docklands area. The ceasefire ended because PIRA were unwilling to begin the decommissioning of their weapons, prior to entering negotiations in the peace process. This requirement for decommissioning was intended to prevent PIRA using violence or the threat of violence, as leverage in the negotiations.

Two men who worked in a newsagents shop were killed in the explosion and two hundred and fifty people were injured.

When President Bill Clinton visited Belfast in November 1995 to lend his support to the peace process and discourage a return to violence, South Armagh PIRA were already preparing for the Docklands bomb attack.

Police investigating the Docklands bombing, recovered fingerprints belonging to one of the terrorists, but at the time they didn’t match any fingerprints that were currently held by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

Following a public appeal for information regarding the type of truck used in the bombing, the police received a call about a truck that fitted the description. The caller had seen the truck in Barking, England.

Police went to the location in Barking that the caller had provided and on waste ground they found evidence that the terrorists had attempted to set fire to some small items, including a magazine and the truck’s tachograph. This was an attempt to destroy forensic evidence, but for some reason, possibly because they were interrupted by members of the public, the items were not burnt. The police managed to lift a thumbprint from the magazine.

After the discovery of the evidence found in Barking, the police were able to track the route of the truck and found another thumbprint in a room at a truck stop in Carlisle and then another thumbprint on a ferry ticket in Stranraer, Scotland. The terrorists had used the ferry from Larne in Northern Ireland to Stranraer in Scotland, to travel over with the truck.

The Operation

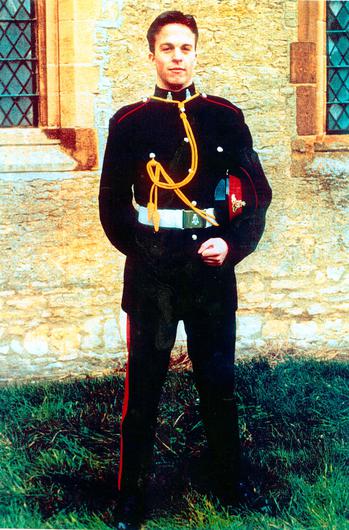

Between August 1992 and February 1997, seven soldiers and two police officers had been murdered in sniper attacks in South Armagh. The ninth victim was Lance Bombardier Stephen Restorick, the last soldier killed during the Troubles.

Stephen was twenty-three years old. He had been manning a vehicle check point (VCP) in Bessbrook, County Armagh. Stephen had been talking to a woman in a car at the VCP and was smiling as he handed back her driver’s licence. Stephen was shot by a sniper armed with a high velocity rifle. The woman in the car narrowly escaped death when the bullet skimmed her forehead.

Early in the afternoon of the 10th April 1997, as a result of a prolonged surveillance operation directed against a PIRA unit responsible for at least some of the nine murders, four members of PIRA were arrested during a raid on a farmhouse.

Two unmarked vehicles carrying sixteen British soldiers arrived at the farmhouse. There were two soldiers in plain clothes in the front of each vehicle and a further six uniformed soldiers in the rear of both vehicles. RUC officers arrived shortly after the military.

The four terrorists were caught completely off-guard. They clearly didn’t expect the sudden arrival of military and police personnel. When soldiers entered the barn they found three very startled PIRA terrorists: Martin Mines, James McArdle and Bernard McGinn.

The three terrorists were standing near to a Mazda car that had originally been a maroon colour but was repainted blue. The car also had false number plates. Inside the car was a CB radio and behind the rear seat was a metal platform upon which a sniper could fire a rifle, whilst lying down, with the hatch and tailgate open. After firing the rifle, the hatch and tailgate would be closed quickly and steel plates attached to the platform would provide some cover from any return fire.

The following photograph is a view from inside a vehicle, adapted by the IRA for use by a sniper:

A fourth terrorist, Michael Caraher was spotted walking between two buildings. Caraher attempted to run away but was pursued and apprehended by two soldiers. Caraher gave a false name and provided an excuse for his presence at the farm. When questioned shortly after by an RUC constable, Caraher didn’t respond when asked why he ran away, or why he hid in gorse bushes, or why he was wearing two layers of clothing on a warm day.

Caraher was wearing khaki coloured overalls with a jacket, pullover and jeans underneath (Other members of the terrorist cell were also wearing two layers of clothing). To the untrained eye this might seem like normal apparel for people on a farm but overalls or ‘boiler suits’ are also standard kit for terrorists in that part of the world.

When Caraher was searched, a prayer card was found with the name ‘Michael’ on it. When asked again for his name he didn’t answer.

Outside the barn was a Ford Sierra that belonged to Michael Mines. Inside the Sierra was another CB radio. A subsequent forensic examination of the Sierra found traces of PETN in the boot of the car, which is a component of explosives such as Semtex. The car previously had false number plates attached. A mobile phone found in the car and another one in the barn were only capable of receiving calls, neither could make out-going calls.

Also inside the barn was a small cattle trailer with straw on the floor. A wheel was missing and there was some damage to the axle. There was a mark on the road next to the farm and the mark led into the barn. The trailer had obviously be towed along the road for a couple of hundred yards and into the farm, whilst the wheel was missing. There was a hidden compartment in the floor of the trailer, inside which was an AKM rifle and a Browning .50 inch calibre rifle with a telescopic sight attached and a magazine containing three rounds. An additional fifty rounds of .50 ammunition was found.

The wooden panel under which the rifles were hidden, was attached to the frame by a single nut and bolt. Michael Caraher and James McArdle were both found to be carrying a spanner that was the appropriate size for the nut on the panel.

On the day prior to the raid on the farm, PIRA terrorists had used the car and trailer during an attempt to murder a member of the security forces in a sniper attack. When the terrorists were unsuccessful in finding an opportunity to commit a murder they aborted the planned attack.

Whilst driving away, possibly with the intention of crossing the border, one of the wheels came off the trailer. The terrorists were forced to take the car and trailer to the farm rather than cross the border into the Republic of Ireland. They left the car and trailer in the barn overnight and returned the next day.

What the four terrorists didn’t realise was that the wheel coming off hadn’t just been a stroke of bad luck. The military had covertly accessed the trailer and loosened the wheel nuts.

When the four terrorists returned to the farm the next day, the military and RUC had arranged a surprise for them.

When the four terrorists were fingerprinted later that day, the fingerprints of James McArdle produced a match for the thumbprints retrieved during the Docklands bombing investigation.

It didn’t come as a surprise that PIRA in South Armagh had been involved in the Docklands bomb attack. The terrorist attack had their metaphorical fingerprints all over it and thanks to McArdle, also his actual fingerprints.

Politics & Elastic Morals

In a news article that you can read HERE about the conviction and sentencing of the four terrorists in 1999, you can see that they received a total of six hundred years imprisonment for a variety of offences. They laughed and shouted to friends and family in the court.

Thanks to the terms of the ‘Good Friday / Belfast Agreement’ and the early release of terrorist prisoners, the four terrorists knew they would be eligible for release within sixteen months. A couple of months prior to this, the Irish government had barred four terrorists from benefiting from the early release scheme. They had been involved in the 1996 murder of a police officer, Garda Jerry McCabe. As you see in a news article HERE, there was controversy in 2004, regarding the release of those terrorists.

In a news article that you can read HERE, you will see that in the year 2000, the then Northern Ireland Secretary of State Peter Mandelson, used the royal prerogative to allow McArdle to leave prison at the same time as the other three terrorists. McArdle could have been detained for two years but apparently someone at the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) thought that wasn’t a sufficiently short enough sentence.

In another news article that you can read HERE, you can read about some of the crimes the four terrorists committed and the prison sentences they were given. You will also see that Bernard McGinn broke under questioning and claimed to police that it was Michael Caraher who was the sniper. McGinn claimed that his role was to ‘ride shotgun’.

The police lacked the evidence necessary to prosecute Caraher and the judge ruled his statement as being inadmissible. Caraher did receive lengthy prison sentences on a number of other charges, including the attempted murder of an RUC officer at Forkhill in South Armagh. The officer had sustained a severe injury when he was shot in the leg.

Bernard McGinn was found guilty of murdering Lance Bombardier Stephen Restorick. He was also found guilty of murdering Lance Bombardier Garrett in December 1993 and Thomas Johnston, a former member of the Ulster Defence Regiment, in August 1978. McGinn was also convicted for his role in mixing the explosives used in bomb attacks including the explosions at the Baltic Exchange and Docklands.

McGinn died in December 2013, it would appear from natural causes. You can read an article HERE.

Thanks for taking the time to read this blog and I hope you found it interesting. There are numerous other blogs available. Just take a look at the menu, click and read.#

You can also find me on Twitter (X) at @SageDespatches